Dalka’s history

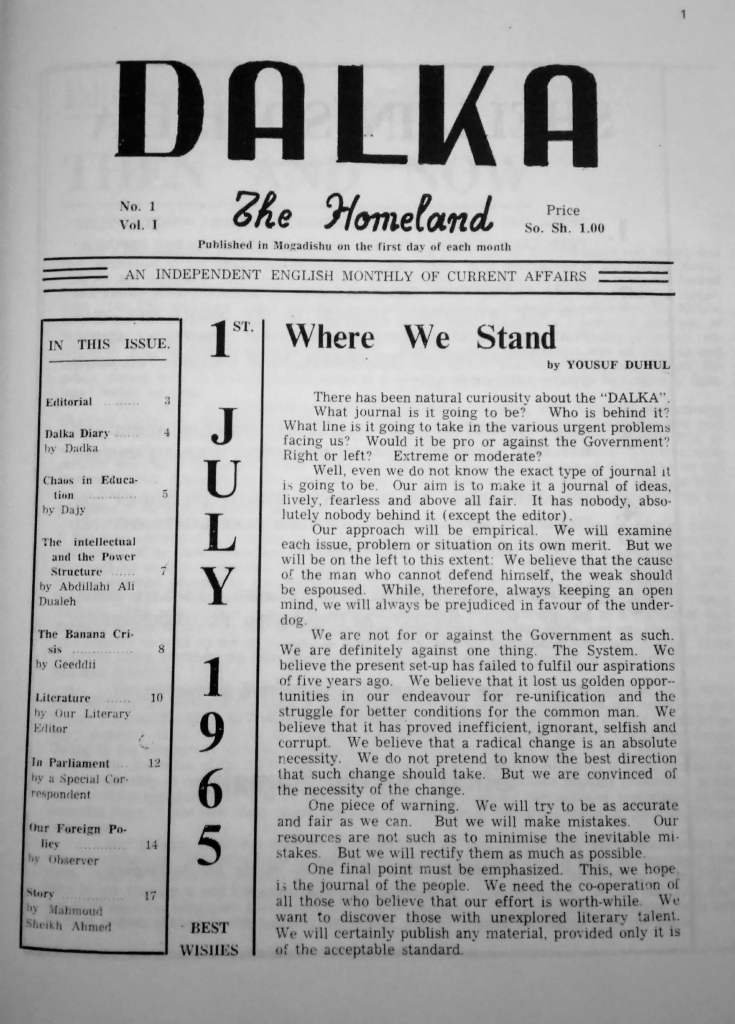

Dalka was launched on 1 July 1965, as a current affairs magazine in the Somali capital, Mogadishu. Owned and edited by Yousuf Duhul—a UK-trained Somali lawyer in private practice—the monthly (later bi-monthly) proved popular with the educated and literate classes.

The publication, as the editor recalled decades later, was in all respects ‘a child of its time’ (1). This fact was reflected no less in its very name which, to the Somali ear, evokes positive connotations of ‘the homeland’ (2) and which, to the generation who still recall flicking through its pages almost half a century ago, its name is synonymous with “the good old days!” By its very existence, the journal epitomised the euphoria which swept across the Africa in the 1960s, in which the continent’s newly-independent citizens (the editor and contributors no less) placed high hopes on the grand possibilities self-government would hold.

Within that context then, the journal’s raison d’être seemed simple enough: ‘Our aim is to make it a journal of ideas, lively, fearless, and above all, fair… We will examine each issue, problem or situation on its own merit’ (3), read the editorial of the first ever edition.

Many of the contributors were drawn from a group of like-minded young men in their twenties and thirties, many of whom—like the editor—had studied in the UK or less commonly, elsewhere in the Anglophone world, such as in the United States.

That these writers devoted so many lines to the censure, not only of the government and the Parliament but also their individual members, could only have been welcomed. Unsurprisingly, as one of those ‘peripherally’ involved in the publication recently told me, Dalka soon proved to be a ‘thorn in their [i.e. politicians’] side’, scrutinising their activities—and more often than not, lacking of propriety and dutifulness in executing these duties. Although it often made very uncomfortable reading for the nation’s politicians, it was perhaps to their credit that despite having the power to inhibit it, it was only much later that the powers that be pursued such a course.

Still, since Somali democracy was still a largely untested venture by the mid-1960s, most contributors wrote from behind the veil of pseudonyms. This was perhaps a decision largely driven by pragmatism: since many of them worked for the government and wrote their criticisms of it by night, the authors quite naturally did not want their articles to imperil their employment.

Apart from the main political articles, Dalka also carried short stories as well as pieces on subjects as varied as literature and foreign relations, from prolific contributors. Letters from readers, showcased on the ‘Correspondence pages, were a nod to the publication’s wide-ranging readership with messages finding their way onto the pages from as far afield as Washington D.C., Geneva, the Hague, Aberdeen and Bremen in West Germany.

Writing in the era before the pimple outbreak of military coups and regimes would afflict the continent, Duhul and co enjoyed the liberty of a free press, a luxury to which they and many of their African counterparts would soon wave goodbye. The magazine was in continual publication for two years, between 1965 and 1967, before it became increasingly difficult to produce any non-government publications, with the Government of the day slowly but surely buying out the small independent press.

It was briefly revived in no less a pivotal month in modern Somali history than October 1969, in which not only the incumbent President was assassinated but a military takeover was staged. Two editions—issued on the first and fifteenth of the month—were to be the last, with the incoming military regime ‘putting paid to any notion of free speech’ (4).

The first of its kind, as an independent journal, it spawned other similar publications such as the Italian-language competitor, La Tribuna under the able editorship of Ismail Jimale Ossoble, another lawyer by profession but who also served briefly as a parliamentarian and minister between the elections of 1969 and the coup of the same year.

——-

(1) Yousuf Duhul, ‘Preface’, Dalka: ‘The Homeland’: Documents from a Free Somalia Press, Facsimile Edition, vol. I, 1965 (London: HAAN Publishing, 1997), p. vii.

(2) ‘The homeland’ is the literal, and conveniently idiomatic, translation of ‘Dalka’, since it conveys similar impressions to its Somali opposite number.

(3) Dalka, vol. I, no. 1, 1 July 1965, p. 1.

(4) A.S.A., ‘Foreword’, Dalka: ‘The Homeland’: Documents from a Free Somalia Press, Facsimile Edition, vol. I, 1965 (London: HAAN Publishing, 1997), p. vi. In preparing this page, I have made extensive use of this Foreword.